When Regulators Fail, the Courts Are the Last Refuge for Bull Trout

From high mountain streams to the deep expanse of Lake Pend Oreille, waterways shape our communities, our economy, and our identity in North Idaho. They are also the lifeblood of one of the Northwest’s most imperiled native fish: bull trout.

Today, our region’s bull trout are under great threat—not because we lack laws to protect them, but because the agencies charged with enforcing those laws have failed to do so. That failure, along with the developers disregard for the minimal conditions they were told to follow, has left us with no meaningful option other than litigation.

The Idaho Club’s proposed marina and high end housing development near the mouth of Trestle Creek is at the heart of the problem. This development would excavate thousands of cubic yards of material, build a large and busy commercial marina, install a massive breakwater, reshape shoreline, build seven high end waterfront homes, and drive hundreds of steel piles into the lakebed—all immediately adjacent to a critical bull trout spawning stream.

Trestle Creek is not just another stream. It is one of the most important spawning tributaries to Lake Pend Oreille. In some years, nearly half of all documented bull trout redds—or egg nests—in the entire basin have been counted there. Bull trout migrate between the lake and Trestle Creek multiple times throughout their lives. Juveniles are raised in the creek’s cold, clean waters before moving into the lake. Both the creek and the lake are designated critical habitat for bull trout under the Endangered Species Act.

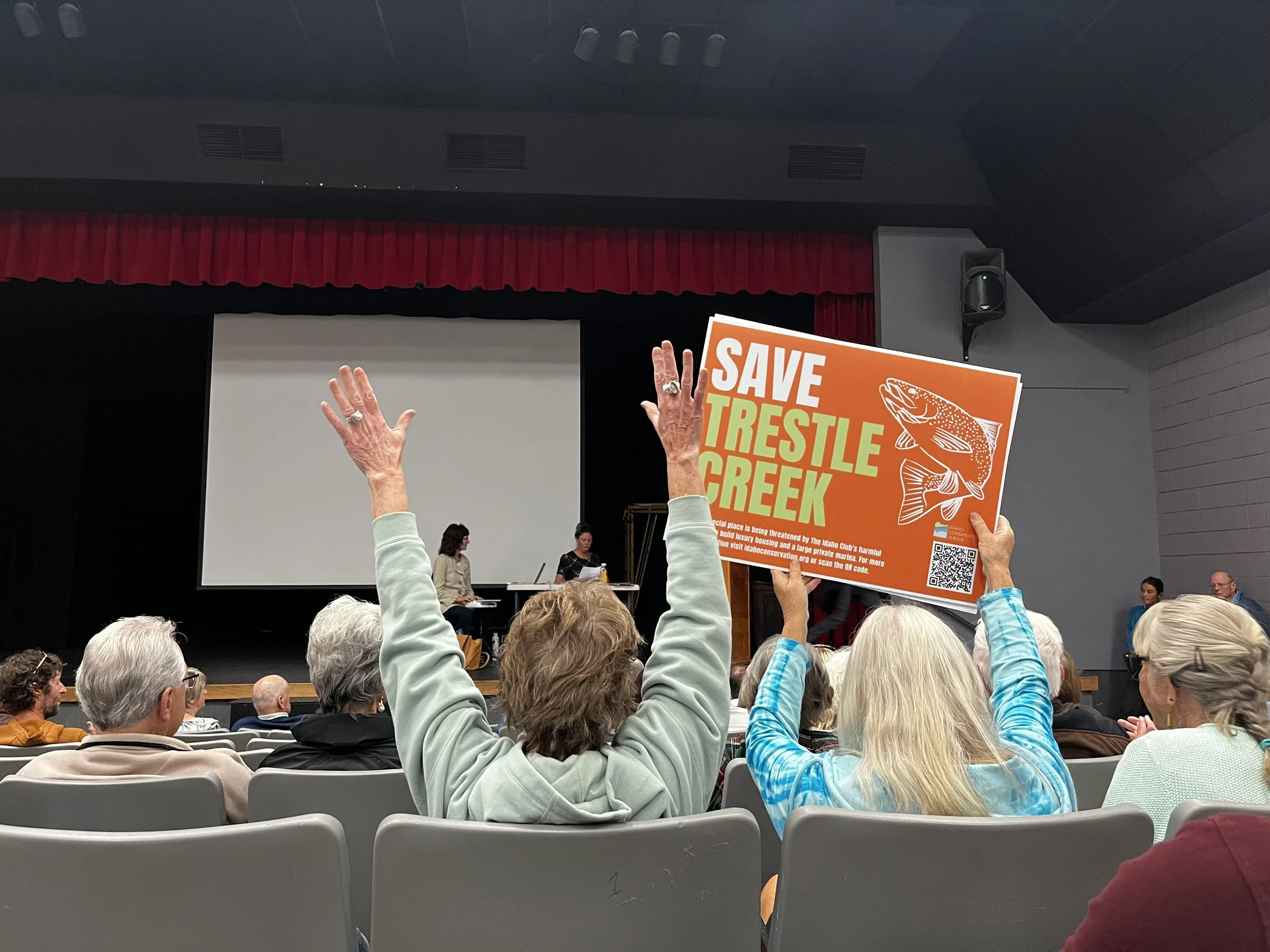

The Idaho Conservation League and our partners at the Center for Biological Diversity have gone to court over the Idaho Club’s marina and lakeside development because there is no other choice if we are to save bull trout in Lake Pend Oreille. The developer and the regulating agencies—the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Corps) and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service—failed to follow the law designed to protect a threatened species on the brink of extinction.

In late 2024, the Corps’ own Biological Assessment concluded the project was “likely to adversely affect” bull trout and their critical habitat. That finding should have triggered formal consultation under the Endangered Species Act and required a detailed biological opinion, complete with enforceable mitigation measures and limits on harm.

Instead, after the developer proposed revisions to the Biological Assessment and made “firm commitments” about timing and construction methods, the Corps reversed course. It declared the project “not likely to adversely affect” bull trout. The Fish and Wildlife Service concurred. Formal consultation was abandoned. No biological opinion. No incidental take statement. No robust, science-based guardrails on the development.

This abrupt flip ignored troubling facts the agencies had already acknowledged: that Trestle Creek is a core spawning stream; that bull trout migrate through the development area; that pile driving, sediment, boat traffic, and shoreline hardening can stress fish and increase predation; and that marina structures create shaded ambush habitat for invasive predators like northern pike and walleye.

Equally troubling, the agencies failed to take the required “hard look” under the National Environmental Policy Act. The Environmental Assessment barely analyzed wildlife impacts. It did not grapple with increased boat traffic at the mouth of Trestle Creek. It did not consider how nearly 100 boats, additional docks, shoreline armoring, and new residential development would compound existing stressors in a system where redd counts are already declining sharply.

But even that flawed approval process is not the end of the story.

The permit contains clear, explicit conditions. The North Branch reroute was required to occur only during no-flow or dry conditions—typically late summer or fall—and had to be completed before marina construction began. Those conditions were central to the agencies’ conclusion that impacts would be limited.

Yet construction began and continued during a historic rainfall event. Heavy equipment was observed dredging the marina basin before the reroute was completed. The Corps issued a letter of non-compliance, confirming that work was occurring out of sequence and in violation of permit terms. However, they later allowed the construction to resume.

Those violations are not technicalities. They represent a willful disregard for the conditions that were required, and the agencies’ lack of willingness to enforce those very reasonable conditions is reprehensible.

Litigation is always our last resort. We spent years engaging in the administrative process with state and federal agencies, as well as Bonner County. We raised scientific concerns. We pointed out legal deficiencies. We urged stronger safeguards for bull trout. We watched as the agencies themselves initially concluded the project would adversely affect bull trout—only to retreat from that position.

The agencies ignored their own experts, discounted their own prior findings, and allowed construction to proceed in violation of permit conditions.

Bull trout have already vanished from much of their historic range. In the Lake Pend Oreille basin, redd counts in Trestle Creek have dropped dramatically in recent years. We are watching the erosion of a once-robust population.

Our lawsuit asks the court to set aside the unlawful approvals, require reinitiated consultation, and ensure that bull trout and their critical habitat are protected. It aims to stop development that cuts into the heart of a critical spawning stream. We went to court because nothing else worked. And because once bull trout are gone, no lawsuit can bring them back.

In North Idaho, we pride ourselves on stewardship. If we cannot defend one of our most iconic native fish in one of its most important remaining strongholds, what does that say about our commitment to future generations?