SAVE THE SOUTH FORK SALMON

Cyanide-leach Stibnite mine threatens Idaho’s clean water, outdoor heritage

The South Fork Salmon River is one of Idaho’s most pristine and ecologically important watersheds, providing clean water for Idaho and beyond our borders. It’s world-renowned for its whitewater boating and provides wild and free-flowing water that salmon, steelhead, and bull trout need to survive.

This is no place for a massive open-pit cyanide leach mine called the Stibnite Gold Project. While we all use and need minerals, this mine poses an unacceptable risk to one of Idaho’s most cherished places. Cyanide-leach mining has a dismal track record for failures.

We have entered a critical phase in this decades-long battle. NOW is the time for Idahoans to speak up.

Will you stand with us?

John Robison, ICL Public Lands & Wildlife Director

“The Stibnite Gold Project is the equivalent of high-risk, open heart surgery for the East Fork South Fork Salmon River, and the watershed will be worse off as a result, not better.”

Josh Johnson, ICL Central Idaho Director

”Perpetua Resources is making a concerted effort to pitch this mine as necessary due to the antimony reserves at Stibnite. However, this PR campaign is designed to obscure what Stibnite really is—an irresponsible proposal for an environmentally damaging open-pit gold mine in the headwaters of the South Fork of the Salmon River.”

Get to Know the Special Places at Stake

A Journey Through Burntlog

Witness this special place—and fight for it—before it’s lost forever

The East Fork South Fork Salmon River is many things—a rambunctious whitewater river; a stronghold for bull trout, steelhead, and Chinook salmon; and the target for an open-pit mine. Mining company Perpetua Resources hopes to dewater the river, divert it into a tunnel, excavate a 400’ deep pit under the riverbed, and then backfill the pit with mining waste from another open pit. Meanwhile, pristine tributaries to the East Fork South Fork would be buried under 400’ of toxic mine tailings and waste rock. The footprint of the proposed Stibnite Gold Project goes far beyond the footprint of previous mining operations and will have unacceptable impacts both onsite and far downstream.

Perpetua Resources’ preferred road for the mine, the so called Burntlog Route, would punch a 40-mile long high-elevation industrial haul route through Inventoried Roadless Areas on the western flank of the Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness. Its route would cut through important denning habitat for wolverine and cross streams that provide habitat for endangered bull trout, Chinook salmon, and steelhead. Given that hundreds of truckloads carrying hazardous chemicals and waste would be transported via this route, it spells big trouble for Idaho’s backcountry—and all who rely on and love it.

In fall of 2025, ICL staff headed into the South Fork Salmon River watershed country to explore some of the special places at grim risk of the Stibnite Gold Project and the Burntlog Route. From watching dozens of spawning Chinook salmon to weathering an overnight thunderstorm, their experience was just like the landscape—rugged, wild, and worth fighting for.

Continue reading to take A Journey Through Burntlog.

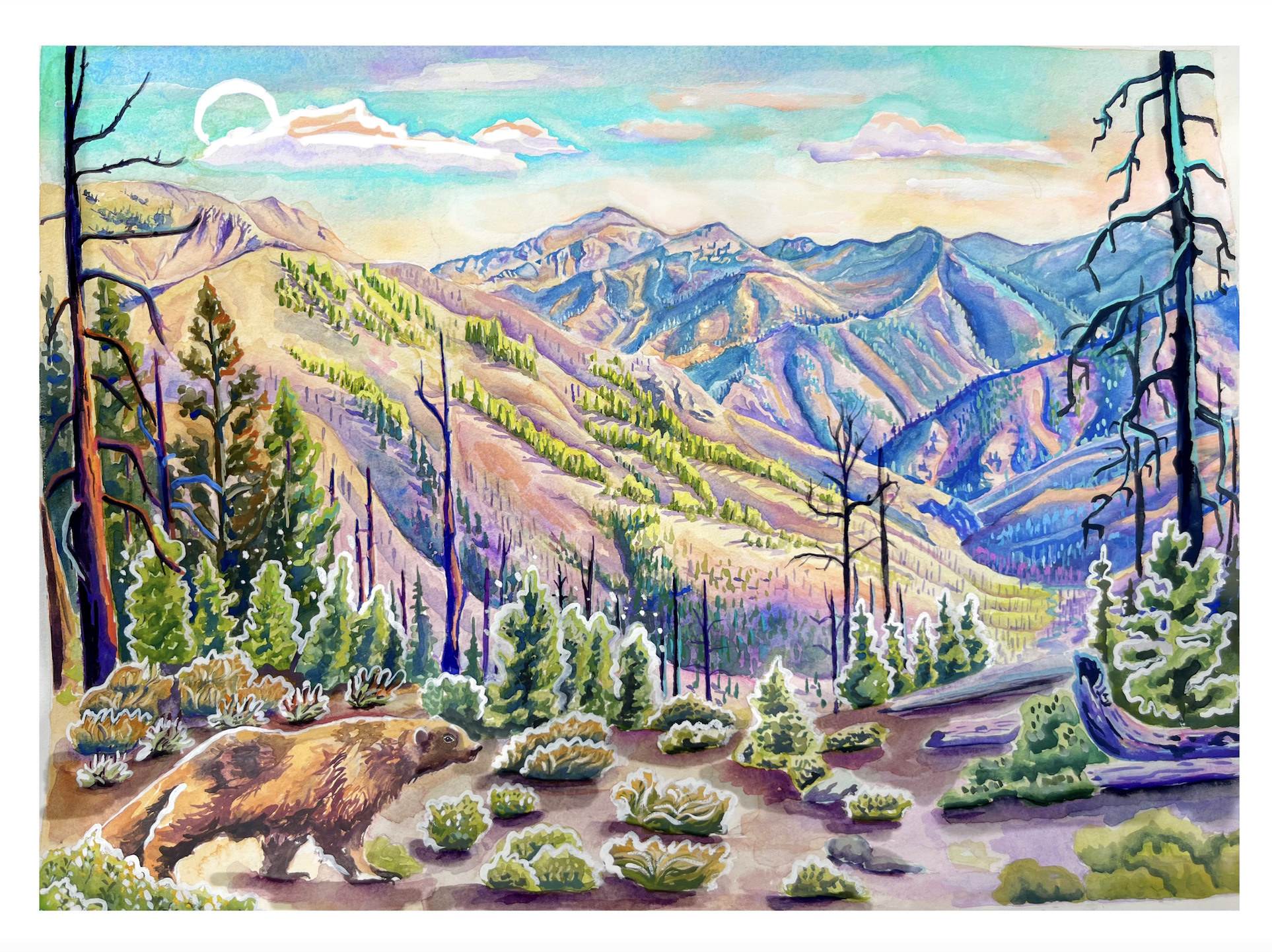

Art by Jasper Vanspoore, ICL’s 2025-2026 Artist in Residence.

A Journey Through Burntlog

by Jeff Abrams & Abby Urbanek

The proposed Stibnite Gold Project threatens many special places. Some of those places are well-known, like the South Fork Salmon River—a place where Idahoans can hunt, fish, take their kids to watch wild salmon spawn, and simply be in nature. Other threatened places, however, are a little less known—places like the Burnt Log, Black Lake, Meadow Creek, and Horse Heaven Inventoried Roadless Areas (IRAs), and the Chilkoot Research Natural Area.

While there may be fewer Idahoans that know these places, that doesn’t mean they aren’t worth fighting for.

This fall, ICL staff members Jeff Abrams and Abby Urbanek set out to get to know some of these places a little better. They weren’t disappointed.

Morning. Monday, Sept. 8. McCall, Idaho.

Journal 1

After coffee, a hearty breakfast, and playing with Jeff’s 5-month-old black lab Rooney, we moseyed out of McCall in the late morning, bound for the Black Lake Inventoried Roadless Area (IRA). This landscape, which borders the Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness, is one of the four IRAs threatened by Perpetua Resources’ proposed Burntlog Route.

The sun was high and bright, making the first stretch of the drive pass quickly. We wound along the South Fork Salmon River road, glancing into the shimmering water below. After spotting a Chinook salmon carcass, we grew antsy to stop and look for more.

The road dipped gently down the valley and hugged the river, where we pulled over at a quiet spot and scrambled onto a few logs between the road and riverbank. From there, we enjoyed the show.

First there were five. Then, as our eyes adjusted to the water, five became fifteen—wild summer Chinook, home at last. It was the most salmon I’ve seen in my entire life. The journey these fish take from their home waters to the ocean and back again is nothing short of miraculous—and something that Idahoans are incredibly lucky to witness.

We watched in awe for nearly half an hour as females riffled the gravel and males jockeyed for position. Our quiet conversation turned to the Stibnite Gold Project and what it could mean for these fish—their habitat, their survival, their legacy. If the Stibnite Gold Project comes to fruition, the mine will bleed pollution into this river for centuries to come, long after this senseless and short-sighted gold mining operation is over.

After pulling ourselves away from the show, we continued driving to the confluence of the East Fork South Fork Salmon River and Johnson Creek. Both the South Fork Salmon River and Johnson Creek, as well as Burntlog Creek, are the three streams deemed eligible for protection under the National Wild and Scenic River System by the U.S. Forest Service. The Stibnite Gold Project spells trouble for each of them.

Whether by providing habitat for endangered salmon or bull trout, or for their recreational or historic features, these waters have been recognized for the remarkable values they possess. These streams—and the values and experiences they hold—are worth protecting.

I can’t understand why some would trade healthy rivers and enduring salmon runs for short-term profit that will leave the place worse off, even by the Forest Service’s own reckoning. A few wealthy investors might benefit today, but future generations will suffer the consequences of perpetually polluted streams bereft of salmon.

Noon. Monday, Sept. 8.

Journal 2

We stopped for lunch at the South Fork and the East Fork South Fork confluence, some 30 road-miles downstream from the Warm Lake Highway turnoff. The steep, twisted canyon walls under the Williams Peak Lookout seem to elicit the question… “which river is flowing into which?” The salmon and steelhead that return to these two watersheds, of course, know this answer, instinctually.

We take a right turn and begin heading upstream along the East Fork, bisecting opposite flanks of the mountains. Many ridgelines above us ascend over 3,000 feet from the river in just over a mile. Avalanches that thunder down from those mountaintops have been known to deposit up to 100 feet of snow, mud, gravel and matchstick timber into the East Fork, closing large sections of the river road. In 2019, water backed up behind slide debris, topping the river banks and washing out several hundred yards of the road.

Further upstream, we stopped at another roaring convergence of waterways where Johnson Creek joins the East Fork, near Yellow Pine. It’s here, in the deep waters below, that many anglers who travel from all corners of the country, finish their quest to hook an elusive bull trout after leapfrogging their way up the riffle and pool sections of the East Fork canyon.

It’s difficult to imagine a hundred or so years of backcountry living by looking at the scant remains of the old Stibnite townsite. An interpretive sign proclaims a small, open patch of ground amongst the lodgepoles as “an end of an era”. If only we could all be sure of that. What is not difficult to envision is what would happen to this place if the Stibnite Gold Project is allowed to proceed. The scars adjacent to the townsite appear as stained, ecological skeletons on the steep hillsides and within deep, toxic tailings ponds.

It’s vitally important to remember that Stibnite had been qualified to receive Superfund money and be named to the National Priorities List, but behind the scenes political arm-twisting squelched those efforts to continue a path towards comprehensive site clean-up. Before Canadian speculator Midas Gold purchased a small section of land in the middle of these impacted public lands, the Northwest Power and Conservation Council had also planned to fund a robust restoration project to be led by the Nez Perce Tribe. Now, instead of a federal mine cleanup, we’re on the verge of doubling-down on our original mistake and green-lighting a new, much bigger mine that vastly expands the impacted area for all eternity. And the Burntlog Route would be the literal “avenue” to make it all happen.

Forest Service Road 5037, known as the Thunder Mountain Road, pitches up the East Fork and out of the Stibnite area like an ant trying to escape from the bottom of a mixing bowl. For 15 rugged miles, Abby and I make our way up to and along the ridge that separates the South Fork and the Middle Fork Salmon River drainages. Two hours later we reach the Summit Ridge trailhead that we’ll strike out on first thing the next morning. We’ll camp a mile or two away on a ridgeline underneath the Meadow Creek Lookout. The idea that the primitive USFS road we just followed along the edge of the Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness may be transformed into a 40-mile long industrial backcountry haul route for the annual transport of 6,000,000 gallons of diesel, 4,000 tons of sodium cyanide, explosives and other chemicals is, to us, unfathomable.

The Idaho Conservation League would fight this ill-conceived project even if it wasn’t connected to an equally bad gold mining proposal.

Evening. Monday, Sept. 8.

JOURNAL 3

As night settled over camp, the forest around us began its quiet performance. A symphony of sounds only wild, untouched places can provide. Wind whipped through the lodgepole needles above us, then whistled through the dead, downed trees scattered across the forest floor below, echoing like a faint drum. Somewhere deep in the valley, a lone elk called out—high-pitched, uneasy, a warning to anything that could hear it. Jeff—a longtime, avid elk hunter—listened intently. “Something has him spooked,” Jeff said, which was all it took for my imagination to take over. Moments like these—deep in a landscape away from home—remind you that you are just one small piece of a landscape that is alive. I thought about the elk’s worry until I fell asleep that night.

We were lucky that our night in this stretch of country—blissfully inaccessible except by rough road and stubborn determination—fell the night after a full moon. A September full moon is a Corn Moon, which we joked felt too perfect: Jeff’s raft is named “Random Corn,” and it’s the boat I first learned to row years ago on an ICL trip, granting myself the title “Corn Queen.” After admiring the moon through the spotting scope and planning our route for the next day, I crawled into my tent and Jeff settled into the back of his truck.

Bob Seger wasn’t playing in my dreams, but at 5am, I woke to the sound of thunder. I opened my eyes as a flash lit up my entire tent—immediately followed by another crack of thunder that sounded like it was gaining speed. I sat up and slipped my boots on, as I figured we were up for the day. The storm continued through the morning—brighter flashes, louder cracks, graupel—but finally gave way at around 8am.

This place—a deep, wild corridor between the Middle Fork Salmon River and Johnson Creek watersheds—would be permanently changed if the proposed Burntlog Route and Stibnite Gold Project were built. Moments like these—elk calls echoing through valleys—are the essence of wild places like this. The only disturbances are natural ones like storms rolling across the ridgelines. They’re what we stand to lose if the Burntlog Route and Stibnite Gold Project are built. That “forest symphony” becomes a cacophony of industrial-sized diesel trucks and pounding construction. A place where elk calls travel miles would instead carry the grind of truck traffic. Old stands of trees that survived the last fire would be pushed aside for widening and straightening. Open country for species like wolverine that have called it home for thousands of years would become degraded and changed into yet another place for wildlife to avoid. As it is right now, this landscape is quiet enough to hear, and quiet enough to feel. And that’s exactly why it’s worth fighting for.

Day journal. Tuesday, Sept. 9.

JOURNAL 4

Coffee was on. Abby and I did have to rummage through plastic totes to get at the less essential breakfast staples, though. It always takes a night or two in the mountains to fully exhale, put the confusing, less-than-natural world on hold and eventually settle into the satisfying pace that only comes from reconnecting with wild places. But we had no time to ease into our environs. As we set out on the Summit Trail—post hailstorm—we were on a mission. A mission of mercy. And exoneration. To absolve the good name of the Burntlog backcountry and the Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness from being implicated in the misdeeds of the Stibnite Gold Project.

It was time for the Special Assignments Team to tackle the initial northern leg of the “Journey through Burntlog”. The truck doors closed and we were off.

Our first goal was to hike up the Summit Trail to the highest point on the entire proposed 40-mile route—8650 feet above sea level. The toxic thoroughfare would obliterate a two-mile section of this fine backcountry access trail leading into the north flank of Indian Creek—a major tributary of the Middle Fork.

We had skirted four Inventoried Roadless Areas (IRA) on the way in. Areas identified by the Forest Service as “having wilderness characteristics” that should be “managed for backcountry values and restoration.” Burnt Log, Black Lake, Meadow Creek, Horse Heaven. This haul road would certainly violate the spirit and explicit intent of that language. Now, we were hiking along the very crest between these wild inventoried areas and the Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness—distinguished only by a 16” wide ribbon of bare dirt between the two. A recent Forest Service geophysical analysis seemed to confirm this foolish example of hair-splitting, saying “when considered as an addition to the Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness, the area would complement the extensive opportunities for solitude and primitive recreation in the Wilderness.”

Some would have you believe this ridgeline would be a perfectly suitable industrial corridor for millions of gallons of diesel fuel and gasoline, for chemical reagents, for sulfuric acid, for mercury-laden residual material, for commercial petroleum lubricants and antifreeze products.

The Final Environmental Impact Statement issued by the Forest Service described the “Burntlog Alternative” otherwise. In comparing its anticipated ecological effects to those from an alternate Johnson Creek access route, the Burntlog Alternative would “result in the greatest change in landscape character and scenic quality, primarily due to construction and operation of the Burntlog Route.”

Many of the creeks that wind through the bottoms of these IRAs have been deemed by Congress to be worthy of protections under the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act for having “outstanding remarkable value” for many of the fish species that call those waters home. The route would certainly put these qualities at risk while crossing 37 sections of stream, 26 landslide areas, and nearly 40 avalanche paths.

Additionally, the steep cirques and north-facing hillsides represent critical habitat for wolverines—a reclusive, fiercely independent species listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. Wolverines require a deep, persistent snowpack that lasts well into May, when their kits emerge from the den. Nearly three miles into the journey, as we looked across the Black Lake Cirque, it became apparent why Idaho’s west central mountains are home to some of the most dense clusters of wolverines and dens, compared to other western states. In the recent past, researchers at the Forest Service placed trail cameras near Riordan Lake and Black Lake. A 2010 to 2015 study identified over a dozen individual wolverines in or adjacent to the Stibnite Gold Project area. Another study showed that Black Lake hosted the highest class of wolverine habitat, receiving adequate snowpack, as defined by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service in seven out of seven years.

It’s no wonder that the agency admitted that construction of the mine, the Burntlog Route, and utility corridors would harm wolverines, including potentially denning females, through habitat loss and fragmentation. USFWS also indicated that sedimentation, spills, blasting and other impacts were “likely to adversely affect” and cause “incidental take” of wolverine, as well as fish species such as Chinook salmon, steelhead and bull trout. The Forest Service arrived at similar conclusions, saying the combined effects of the project would have “long-term, adverse impacts” on wolverines.”

Forays into the backcountry seem to always offer tantalizing glimpses into what might await on a return visit. Our quick jaunt along the north section of the proposed Burntlog Route offered us an opportunity for childlike discovery, cemented every bit of understanding about the remarkable values of this jewel on the crown of the Frank, and validated the commitment that ICL and others have made over the past many years to stand in resolve against the potential desecration of this landscape.

For now, we’ll be happy knowing what we documented and observed on behalf of ICL’s supporters and generations of Idahoans that will make personal connections with the wild, rugged places like this. Abby will return to Boise and her beloved Presley. I’ll regroup in McCall and then pack for the second half of the Burntlog journey. From the south, I’ll take you through the high divide that separates the Salmon and Payette watersheds near Landmark, up the USFS #447 road as it winds through big Middle Fork burn country, alpine meadows, historic pack trails, ultimately stopping at a small, intimate fire ring near the East Fork of Burnt Log Creek.

PART II: The Southern Leg

Journal 5

The outpost of Landmark, Idaho, is perched on a wide, imperceptibly sloping crown that breaks the Payette and Salmon River watersheds. To reach this willow-strewn expanse from the west, adventurers would pass Warm Lake and their chance to turn left, down the South Fork Salmon River. A few miles after the crest of Warm Lake Summit, backcountry travelers are presented with a dizzying array of choices as they approach the Landmark “intersection”: 1) take a left and proceed steeply downriver into the Johnson Creek canyon, eventually making their way to Yellow Pine; 2) stay straight, then make a right towards Deadwood Summit, ultimately finding Stanley or reaching the South Fork Payette River; 3) continue easterly, then turn north and head out Forest Service Road 447, otherwise known as the Burnt Log Road—traversing the high flank of rock and lodgepole flats to the west of the Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness.

My choice, that mid-September day, would be door number three—following the same path along Forest Service Road 447 that thousands of industrial trucks might take each year for the next 30—to haul millions of gallons of diesel fuel, heavy solvents and tons of explosives into the site of the proposed Stibnite Gold Mine.

The south end of the proposed Burntlog Route would begin at the start of Road 447, just down the road from the Landmark Ranger Station, built by the Civilian Conservation Corps in 1924. For years, the historic building functioned as the forest supervisor’s summer office when the Payette and Boise National Forests were managed as one. The Forest Service maintains 447 at a Level 3 designation, defined as “usable by prudent driver in a passenger car.” The agency estimates current summertime traffic at…27 passenger vehicles per day. In the winter, the county only plows to Warm Lake and only the most intrepid backcountry skiers and snowmobilers travel this country.

Welcome to the gateway to what might become west-central Idaho’s new-era version of last century’s illustrious Silver Valley mining district. A “Permit to Construct” for the haul road, issued by the Idaho Department of Environmental Quality, allows Perpetua Resources to transport up to 180,000 tons of various materials per day along the Burntlog Route. Idaho Power has plans for a transmission line upgrade, beginning at their substation near Cascade and culminating with a new 10-mile section, punching up the Riordan Creek drainage, traversing ridgelines close to 9,000 feet in elevation. The 140 kV line would be capable of delivering power needs to 80,000 homes and cut through the Meadow Creek and Horse Heaven Inventoried Roadless Areas.

Only a week earlier, Abby and I struck out by Toyota from the mine site to learn more about the sensitive wildlife habitats and backcountry playground threatened by $4,500 gold prices. Now, heading past the north end of the Landmark Airstrip, I can’t help but wonder what additional insights my travels along the southern 20-mile section of the Burntlog Route will bring.

A few miles up Road 447, I pass numerous private and outfitted hunt camps at Mud Lake, near the turnoff for the Snowshoe Summit Trail. The cluster of campers, pickups, and horse trailers highlights the area’s proximity to prime deer and elk habitat in Sand Creek and Artillery Dome, as well as primitive, nonmotorized game management units in Pistol and Honeymoon Creeks, within “The Frank.”

Not more than a mile later, I pass the site of the proposed Burntlog Maintenance Facility. Here, a year-round support operation would provide storage for heavy equipment, an industrial-grade diesel filling station, and sleeping quarters for Perpetua workers. The location would also be one of eight different “borrow sites” along the Burntlog Route (including one right above the Black Lake Cirque) where massive amounts of road-building material would be excavated.

Eventually, I traverse the headwaters of Burnt Log Creek, under a west-facing face topped by a peak known as Little Baldy. Downstream from the bridge I cross, the waters are eligible as a “Wild” river under National Wild and Scenic River System criteria, for nearly 11 miles to where it confluences with Johnson Creek. Burnt Log Creek has been designated as a priority watershed, with Outstandingly Remarkable Values associated with spawning and rearing habitat for wild Chinook salmon, steelhead, cutthroat trout, redband trout, and bull trout.

My camping destination is another five or six or miles up 447, at a switchback above the East Fork Burnt Log Creek. I’ll make a nice tailgate dinner and fall asleep believing with every fiber of my being that this Stibnite Gold thing is so wrong. Tomorrow, after a morning hike with my bow, I’ll complete the rest of the journey up the 447 Road, passing by primitive trails established by USFS biologists to access wolverine camera trap sites and venturing within a stone’s throw of the Chilcoot Research Natural Area—one of two in the project’s Area of Impact.

PART II: The Southern Leg

Journal 6: The End of the Road

The morning walkabout proved eventful. A sizable group of elk was lingering in a south-facing bowl I traversed into from the truck before daylight. If an uppity spike bull hadn’t blown my cover, things may have worked out differently.

After packing up the rig, I crept further up 447 at just the right pace to keep my eyes fixed on the Pistol Creek ridgeline, trying to catch movement of brown and tawny forms seeking cover from the late morning sun. At a sharp switchback I stopped to chat with an area visitor who had seemingly packed up the entire plantation in northern Washington and hauled it into this rugged and remote country. It was another reminder of how much people value wild places like the landscape of Burnt Log and the lengths they’ll go to tap into the experiences they offer. He planned to walk his pack horses some 10 miles into the next drainage for a week, seeking unsuspecting game and solitude. Little did he know that he wasn’t the only hunter-gatherer making use of the area in recent times. Only a half-mile up the draw is a monitoring location that has documented the presence of threatened wolverines on several occasions.

I crested the pass that led into the Trapper Creek drainage, where a father-son party had been staged for a week. Turns out Dad has been traipsing around this country since the 1970s. A mere 600 yards up the ridgeline was the Frank Church Wilderness boundary dotted with ESA-listed whitebark pines that commonly reach 500 years of age or more. The two had a few choice words on the subject of Stibnite.

Gazing into the next drainage from the 8,000-foot pass, the precarious landscape came into stark relief. Altogether, the 40-mile Burntlog Route crosses 26 landslide/rockfall areas and 38 avalanche paths. It’s unimaginable that this narrow, legacy Forest Service byway would be widened to accommodate year-round industrial payloads for the next 30 years. The area where the Forest Service assessed noise impacts to wildlife encompasses over 50,000 acres. Due to the elevational ranges in the South Fork Salmon River watershed, the area is well-known for rain-on-snow events that have obliterated logging roads and impounded highly-productive spawning gravels used by Chinook salmon and steelhead.

This is a rugged, highly sensitive landscape. Yet, the plants and animals that call the area home may not find ranges this hospitable anywhere else.

In addition to wolverines, fishers and boreal owls have been documented using the area. Habitat modeling indicates 22 special status plant species [critically imperiled (S1) or imperiled (S2)] such as Few-Flowered Spikerush (S1), Labrador Tea (S2), may be found along and near the Burntlog Route corridor. Sweetgrass (S1) and Blandow’s helodium (S2) have been found at the bottom of the drainage near Trapper Cr. (S2) and Rannoch-rush (S2), back down the road by Mud Lake.

The 1,300-acre Chilcoot Peak Research Natural Area (RNA) is now over the eastern ridge, less than a mile away. It straddles the FCRNRW (30%) and the Burnt Log Inventoried Roadless Area (70%) and was established to preserve diverse forest habitats supporting subalpine fir, Douglas-fir, and whitebark pine. It’s known for particularly distinctive geographic features supporting a diverse array of other habitat types, including wet meadows, raised ponds, and a mix of stream gradients. The RNA shows no signs of non-native plants, recreational use, or obvious signs of humans.

Due to the anticipated scale of disturbance associated with the haul route, the Forest Service described a wide range of potential habitat-based impacts leading to a reduction of Chilcoot Peak RNA values, including:

Non-native plant species would reduce values in the long term

Changes to the vegetation community composition would result in a loss of research values and ecological conditions within the RNA

Dust could change vegetation conditions and ecological processes

Human caused fires

Ecological processes being upset in the long term by culvert placement

Some 20 miles after departing Landmark, as I reach the last piece of USFS 447, the road constricts like the end of a garter snake’s tail. Fallen logs begin to engulf most of the primitive road that spans no more than 10-12 feet. Small, spring-fed headwater streams form the headwaters of an unnamed tributary of Trapper Creek. These tiny pieces of water often create rearing habitat and cold-water refuges for juvenile fish that move seasonally, based on thermal requirements.

A side junket to the end of a western-sloping ridge line revealed a dramatic view up into the bull trout habitat of the Trapper Creek drainage. Following the watershed east from Trapper Flats, the Summit Trail ridgeline could be seen on the distant horizon, some five redtail miles away. Abby and I were hiking that piece of the Burntlog Route, just last week—yet the terrain between, including our beloved Black Lake Cirque, seemed utterly impassable. The reality, however, was much different. High along the southern slope of the mountain between me and the Summit Trail, my mind could trace the road scar that would complete this section of undisturbed terrain, and link the north and south pieces of the Burntlog Route. The perspective gave a sense of completion, knowing we had hiked or seen over 95% of the proposed route. At the same time, the brutality of the Stibnite Gold endeavor staggered my conscience like nothing in the last week.

The final few steps of anything resembling USFS 447 led to a modest, yet somehow profound fire ring that seemed to say...”road stops here.”

In the weeks and months ahead, the Idaho Conservation League, along with our conservation partners will do everything under the Salmon River sun to ensure that fire ring remains. There are some places where the road SHOULD stop. This piece of backcountry is one of them.

A Place Worth Saving.

The South Fork Salmon River watershed and all it entails—from the elusive wolverines that live there, to the threatened salmon that swim and spawn in its waters, to the people that value this landscape—is one of the places that makes Idaho special. Places like this are what our way of life is based on. We live in Idaho so we are able to enjoy these lands and pass them down to future generations. The Stibnite Gold Project will essentially create a massive toxic landscape at the top of this watershed—if we let them.

The Idaho Conservation League isn’t willing to let that happen. We cannot risk special places like the South Fork Salmon River watershed. We believe that generations of fish and wildlife should continue to call this landscape home, and generations of Idahoans should be able to continue making memories there. Because once these places are gone, they are gone forever.

Idaho’s future is being set today—you can help ensure that Idaho’s way of life stays special, and future generations can enjoy the sights, sounds, and feeling of places like the South Fork Salmon River.

Will you help us save the South Fork?

The Showdown at Stibnite Begins.

We have entered a critical phase in the fight against the Stibnite Gold Mine. The ultimate fate of the mine could be determined over the coming months. Now is the time to step up and join the fight. With your support, we will do everything we can to prevent this destructive mine.