Saving Salmon, Protecting a Way of Life

We often say that, without the work of Tribes, Idaho’s wild salmon and steelhead would be gone. It’s easy to dismiss this as hyperbole, but in this case, it’s not an overstatement. Without the significant contributions of Northwest Tribal Nations in the last 30 years, there’d be no fish left to protect in Idaho.

Historic Losses

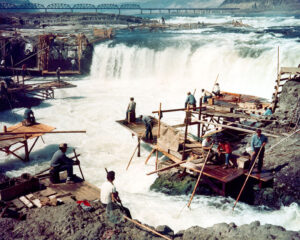

In a history shared by many Tribes who depend on fish, the first people in the Northwest made an everlasting covenant with the salmon. Salmon would give of themselves for the people to eat and to survive through cold winters, and in exchange, the people would look after the salmon. The people ensured they always left some fish in the river to spawn the next generation and that there were always free-flowing rivers in which salmon could swim. The arrival of Europeans to the Northwest endangered this relationship. Settlers sought to extract the wealth of salmon from the region’s rivers. Canneries were built throughout the Columbia River basin, packaging millions of pounds of fish each year to be shipped across the globe. This overfishing decimated salmon populations until harvest was reined in by regulations in the early 20th century. The loss of salmon didn’t stop there. Others then came to exploit Northwest rivers in different ways, as the dam building era began.  Many of these first dams had only crude fish passage or none at all, blocking many populations of fish from reaching their homes. This occurred most notably in the Upper Columbia River with the construction of Grand Coulee Dam. Dams exerted an even greater toll on salmon, driving them toward extinction as the region built its new society and industry on hydropower. For their part, Tribes were forced away from the bountiful rivers and placed on reservations. Through treaties and executive orders, many Tribes reserved the right to hunt and fish. But as fish disappeared, this right meant less and less. As late as the 1970s, federal and state officials sought to limit Tribal fishing, violating these treaties. These efforts were halted in court, but the rapid decline and disappearance of many salmon populations still effectively violated treaties, robbing Tribes of their cultural, economic, and dietary foundation.

Many of these first dams had only crude fish passage or none at all, blocking many populations of fish from reaching their homes. This occurred most notably in the Upper Columbia River with the construction of Grand Coulee Dam. Dams exerted an even greater toll on salmon, driving them toward extinction as the region built its new society and industry on hydropower. For their part, Tribes were forced away from the bountiful rivers and placed on reservations. Through treaties and executive orders, many Tribes reserved the right to hunt and fish. But as fish disappeared, this right meant less and less. As late as the 1970s, federal and state officials sought to limit Tribal fishing, violating these treaties. These efforts were halted in court, but the rapid decline and disappearance of many salmon populations still effectively violated treaties, robbing Tribes of their cultural, economic, and dietary foundation.

Raising the Alarm

By the 1990s, the situation was dire. More than 40% of historical salmon populations had been completely wiped out by harvest and dams. Of the populations that remained, the fish had mostly disappeared, down to just 1% of their historical numbers in many cases. After years of fighting to protect fish under their treaty rights, some Tribes chose a new tool: the Endangered Species Act (ESA). Snake River sockeye were already functionally extinct when the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes decided to submit a petition for listing them under ESA. In 1991, just four wild sockeye came back to Idaho, prompting the Tribes to ask for listing. This proved prophetic, as in 1992, just one male sockeye (the famous “Lonesome Larry”) swam back, and in several of the next years, zero sockeye returned. Listing brought public attention to the issues plaguing all salmon and steelhead in the Columbia River Basin. More importantly, it brought funding and management from the federal government. Federal agencies swiftly worked to ensure that the genetic legacy of Idaho’s sockeye was protected. They captured all the wild sockeye that returned, putting them in a controlled hatchery facility where they could be protected and bred. This program staved off extinction, but the total removal of sockeye from the natural habitat begged a grim question: did salmon still have a home in Northwest rivers? Within just a few years, 12 more populations of salmon and steelhead across the Northwest were also listed under ESA. Tribes were instrumental in submitting many of these listing petitions, and became staunch advocates for urgent, drastic action to save them from extinction. This advocacy resulted in the largest, most expensive species recovery program in history. Northwesterners and the federal government would end up spending nearly $20 billion on salmon recovery from 1992-2022. Without listing under ESA, these funds almost certainly wouldn’t have arrived.

Caretakers of Salmon

Within this vast recovery program that crosses eleven federal agencies, four states, and countless local jurisdictions, Tribes reoccupied their ancestral niche as caretakers and managers of the fish. With Snake River sockeye, the State of Idaho started a program based at Redfish Lake, near Stanley. This program is based largely on fish hatched and raised in hatcheries being released into the lake. The results of these releases have been dismal, as more than 99% of the hatchery-raised salmon fail to survive their migration. The Shoshone-Bannock Tribes started their own program based at Pettit Lake, just upstream of Redfish. Pettit Lake sockeye were completely gone – they hadn’t been observed in the lake in decades. The Tribes first focused on making sure the lake was still a good habitat for salmon. They studied water chemistry and microbiota, and started to enhance the habitat by encouraging growth and supplementing the lakes with nitrogen and phosphorus. After several years of this preparatory work, the Tribes started releasing adult fish into the lake to spawn naturally. Juveniles were hatched and reared in Pettit Lake before migrating downstream. These “natural-origin” fish are better survivors than hatchery fish – of the roughly 4,000 juveniles that left the lake in 2018, 37 adults came back in 2020. The Tribes expect about 100 adults to return in 2023.  These are promising results, though a far cry from both the historic populations and the Tribes’ goals for recovery. Tribal fish biologists admit that they’ve done all they can to improve conditions in Pettit Lake, and that achieving the goals will require significant work further downstream to improve migration – actions like breaching the lower Snake River dams. Still, it’s nothing short of a miracle that Pettit Lake sockeye exist in the wild, and the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes will continue to defend this population and do what’s possible to prevent extinction from happening again. In another part of the state, the Nez Perce Tribe has brought salmon back from the dead. Wild Snake River coho salmon went extinct in 1985, before they could be listed under ESA and protected. More than a quarter of a million adult coho once returned to the Snake River basin every year, spawning in the Clearwater, Grande Ronde, and Lostine rivers. The American Fisheries Society petitioned for listing in the 1970s, but withdrew the effort when federal agencies were ordered to protect dwindling populations across the Northwest in 1980. The federal agencies failed, and coho disappeared. For the Nez Perce Tribe, who’d long relied on the harvest of coho, this was unacceptable. They decided to resurrect coho. In 1995, with a shoestring budget and no state permit for the work, the Tribe released 630,000 juvenile coho in the Clearwater River. The fish grew up, migrated, and came home. The Tribe caught these fish and released their progeny back into the Clearwater, year after year, until they reached their primary goal of 15,000 returning adults in 2014. Since then, they’ve worked to establish natural-origin populations that require no human interference. They’ve also expanded the program to the Lostine and Grande Ronde rivers in Oregon. Read more about the Nez Perce Tribe’s coho program here. While the State of Idaho and federal government have little to do with this effort, both have reaped the benefits. Enough coho return each year to sustain both a Tribal and non-Tribal fishery, generating revenue for local businesses and allowing Idahoans to encounter salmon that were written off long ago.

These are promising results, though a far cry from both the historic populations and the Tribes’ goals for recovery. Tribal fish biologists admit that they’ve done all they can to improve conditions in Pettit Lake, and that achieving the goals will require significant work further downstream to improve migration – actions like breaching the lower Snake River dams. Still, it’s nothing short of a miracle that Pettit Lake sockeye exist in the wild, and the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes will continue to defend this population and do what’s possible to prevent extinction from happening again. In another part of the state, the Nez Perce Tribe has brought salmon back from the dead. Wild Snake River coho salmon went extinct in 1985, before they could be listed under ESA and protected. More than a quarter of a million adult coho once returned to the Snake River basin every year, spawning in the Clearwater, Grande Ronde, and Lostine rivers. The American Fisheries Society petitioned for listing in the 1970s, but withdrew the effort when federal agencies were ordered to protect dwindling populations across the Northwest in 1980. The federal agencies failed, and coho disappeared. For the Nez Perce Tribe, who’d long relied on the harvest of coho, this was unacceptable. They decided to resurrect coho. In 1995, with a shoestring budget and no state permit for the work, the Tribe released 630,000 juvenile coho in the Clearwater River. The fish grew up, migrated, and came home. The Tribe caught these fish and released their progeny back into the Clearwater, year after year, until they reached their primary goal of 15,000 returning adults in 2014. Since then, they’ve worked to establish natural-origin populations that require no human interference. They’ve also expanded the program to the Lostine and Grande Ronde rivers in Oregon. Read more about the Nez Perce Tribe’s coho program here. While the State of Idaho and federal government have little to do with this effort, both have reaped the benefits. Enough coho return each year to sustain both a Tribal and non-Tribal fishery, generating revenue for local businesses and allowing Idahoans to encounter salmon that were written off long ago.  Tribes and Tribal people continue to serve as caretakers and stewards of salmon and steelhead across the state. Besides these miraculous reintroduction efforts, Tribes have worked tirelessly to restore and protect other habitat in Idaho:

Tribes and Tribal people continue to serve as caretakers and stewards of salmon and steelhead across the state. Besides these miraculous reintroduction efforts, Tribes have worked tirelessly to restore and protect other habitat in Idaho:

- The Nez Perce Tribe has completely restored the Crooked River, a tributary of the Clearwater that was dredged in the mid-20th century. The Nez Perce also manage fisheries and habitat on the South Fork Salmon River and Big Creek, a tributary to the Middle Fork Salmon River.

- The Shoshone-Bannock Tribes have transformed Panther Creek and the Yankee Fork, two tributaries of the Salmon River, from barren streams poisoned by mine runoff and dredge tailings into functional habitat for Chinook salmon and steelhead trout. The Tribes have used hatcheries to quickly increase fish populations, but fish are still reared in-stream, ensuring higher survival during migration.

- The Upper Snake River Tribes Foundation (USRT) and their member Tribes have worked collaboratively with Idaho Power and the State of Idaho on a plan and state policy to reestablish salmon and steelhead into the Mid-Snake River, habitat that’s been blocked since the 1950s. USRT has made significant progress toward programs that would bring fish back into these areas for ceremonial harvest – a first step on the road toward fulfilling the promises made to these Tribes long ago.

These streams and others, collectively, now make up the best salmon habitat left in the lower 48 states. This paradise wouldn’t be possible without the efforts of Tribes to improve and defend these places, and we expect them to continue serving as the protectors of rivers, salmon, and steelhead. All Idahoans, and everyone who cares about our state’s rivers and fish, owe Tribal Nations massive thanks for upholding their covenant with salmon. Now it’s time for us to uphold our nation’s covenant with Tribes.