A Long Time Coming: Wolverines get ESA Protection in Lower 48

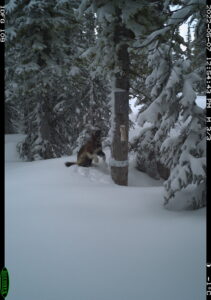

Conjure up an image of a reclusive creature with the profile of a giant armadillo, the proportions and grace of a river otter, and the thick mane of a grizzly. As if dropped out of one’s imagination or taken from the crayon-scribbled colorings of our childhood, the North American wolverine is a perfect mish-mash of our most fanciful wildlife dreams, come to life for real. And, at long last, the creature, in all its untamed wildness, has been protected under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). This summer will mark the 30th anniversary that conservation groups from around the west initially petitioned for the wolverine—the largest terrestrial member of the weasel family in the northern hemisphere—to be afforded ESA status. Now, six court cases later, confronting a rapidly-warming planet and human recreation activities that penetrate into increasingly remote backcountry refuges, wolverines have been given a critical lifeline to reverse significant population declines. News of the decision, issued by U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS) this week, was presaged in a Species Status Assessment on North American wolverine released by the agency in September. The Idaho Conservation League is extremely gratified by this long-overdue determination and is appreciative that undaunted, sustained conservation efforts, led by Earthjustice and others, have resulted in this action. Among the primary justifications cited by USFWS in its listing decision was the acknowledgement that uncertainties cited in earlier ESA findings around climate change and its effect on the viability of wolverines have essentially been resolved. In fact, the USFWS went as far as to say “climate change also has the potential to exacerbate the impacts (to wolverines) of other stressors, including effects from roads, winter recreational activity, development, low genetic diversity and small populations.” In other words, the science about our changing climate and its implications to wolverines and other highly vulnerable native wildlife is settled.Wolverines require large, isolated, undisturbed tracts of wild country—particularly during winter, when they use deep, high-elevation snowpack to den and rear their kits. While females can occupy up to 150 sq. miles of this highly-specific habitat, lone males have been known to use home ranges almost four times that size. Once ranging well into the southern Rockies and west to the Sierras of California, core populations of wolverines now persist only in relatively small, wild, alpine pockets in Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, Washington and northeast Oregon. Across all the vast high-elevation expanses of the American west, their numbers barely reach 300 individuals.

This summer will mark the 30th anniversary that conservation groups from around the west initially petitioned for the wolverine—the largest terrestrial member of the weasel family in the northern hemisphere—to be afforded ESA status. Now, six court cases later, confronting a rapidly-warming planet and human recreation activities that penetrate into increasingly remote backcountry refuges, wolverines have been given a critical lifeline to reverse significant population declines. News of the decision, issued by U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS) this week, was presaged in a Species Status Assessment on North American wolverine released by the agency in September. The Idaho Conservation League is extremely gratified by this long-overdue determination and is appreciative that undaunted, sustained conservation efforts, led by Earthjustice and others, have resulted in this action. Among the primary justifications cited by USFWS in its listing decision was the acknowledgement that uncertainties cited in earlier ESA findings around climate change and its effect on the viability of wolverines have essentially been resolved. In fact, the USFWS went as far as to say “climate change also has the potential to exacerbate the impacts (to wolverines) of other stressors, including effects from roads, winter recreational activity, development, low genetic diversity and small populations.” In other words, the science about our changing climate and its implications to wolverines and other highly vulnerable native wildlife is settled.Wolverines require large, isolated, undisturbed tracts of wild country—particularly during winter, when they use deep, high-elevation snowpack to den and rear their kits. While females can occupy up to 150 sq. miles of this highly-specific habitat, lone males have been known to use home ranges almost four times that size. Once ranging well into the southern Rockies and west to the Sierras of California, core populations of wolverines now persist only in relatively small, wild, alpine pockets in Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, Washington and northeast Oregon. Across all the vast high-elevation expanses of the American west, their numbers barely reach 300 individuals. Just as the Middle Fork Salmon River hosts undammed, highest-of-quality spawning gravels for endangered Snake River Chinook salmon, the mountain ranges of Idaho’s central and northern wild country remain as some of the most realistic hinterlands for successful expansion of wolverine populations. Large sections of designated Wilderness, recommended Wilderness and Inventoried Roadless Areas are indispensable to sustaining healthy, genetically diverse wolverine populations that can disperse across the broader landscape. The windswept alpine cirques within Idaho’s backcountry offer core wolverine habitat for climate resiliency, possessing abundant late winter and early spring snowpack, prime denning sites, and a variety of food sources.In addition to the effects of climate change, the USFWS also found that the increasing human presence in core wolverine habitat also presents a source of concern for wolverines, particularly with more people moving to and visiting Idaho.The good news is many of the potential impacts to wolverines from recreational and development activities can be avoided or minimized through mindful travel and recreation on the landscape and with science-based travel management plans. For instance, the Idaho Panhandle National Forest is close to approving a plan that strikes a balance between winter recreation and the need to provide denning wolverines a refuge from disturbance. For six winters, the Payette National Forest—where the presence of wolverines has been well-documented—was part of a study monitoring effects of winter travel on wolverine movement. As a result of this work, forest managers on the Payette will be able to customize travel planning decisions using site-specific data on places that wolverines frequent and places they generally don’t use, providing increased certainty for both wolverines and recreationists. In the wake of the USFWS finding, ICL will also be reiterating previous concerns that we must make smart land management decisions that don’t impair areas previously identified as key wolverine habitat—such as the Johnson Creek drainage in west-central Idaho, where 18 miles of new road construction is planned to access the proposed Stibnite Gold Project next to the Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness. The “Burntlog Route” would create an industrial byway for mine traffic 8000 feet high in Idaho’s backcountry and likely reduce the suitability of that area for wolverine. Such impacts from roads and development are well-described in the Species Status Assessment report.

Just as the Middle Fork Salmon River hosts undammed, highest-of-quality spawning gravels for endangered Snake River Chinook salmon, the mountain ranges of Idaho’s central and northern wild country remain as some of the most realistic hinterlands for successful expansion of wolverine populations. Large sections of designated Wilderness, recommended Wilderness and Inventoried Roadless Areas are indispensable to sustaining healthy, genetically diverse wolverine populations that can disperse across the broader landscape. The windswept alpine cirques within Idaho’s backcountry offer core wolverine habitat for climate resiliency, possessing abundant late winter and early spring snowpack, prime denning sites, and a variety of food sources.In addition to the effects of climate change, the USFWS also found that the increasing human presence in core wolverine habitat also presents a source of concern for wolverines, particularly with more people moving to and visiting Idaho.The good news is many of the potential impacts to wolverines from recreational and development activities can be avoided or minimized through mindful travel and recreation on the landscape and with science-based travel management plans. For instance, the Idaho Panhandle National Forest is close to approving a plan that strikes a balance between winter recreation and the need to provide denning wolverines a refuge from disturbance. For six winters, the Payette National Forest—where the presence of wolverines has been well-documented—was part of a study monitoring effects of winter travel on wolverine movement. As a result of this work, forest managers on the Payette will be able to customize travel planning decisions using site-specific data on places that wolverines frequent and places they generally don’t use, providing increased certainty for both wolverines and recreationists. In the wake of the USFWS finding, ICL will also be reiterating previous concerns that we must make smart land management decisions that don’t impair areas previously identified as key wolverine habitat—such as the Johnson Creek drainage in west-central Idaho, where 18 miles of new road construction is planned to access the proposed Stibnite Gold Project next to the Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness. The “Burntlog Route” would create an industrial byway for mine traffic 8000 feet high in Idaho’s backcountry and likely reduce the suitability of that area for wolverine. Such impacts from roads and development are well-described in the Species Status Assessment report. ICL is troubled that the current listing proposal includes an exemption, allowing for the lawful “take” of a wolverine if it is incidentally injured or killed by traps intended to target other species. Since 1995, 11 wolverines have been accidentally captured in traps in Idaho, resulting in three mortalities. We also know that many of these events go unreported. We’ll be encouraging the USFWS to consider these issues and others as they draft a North American Wolverine Recovery Plan—the guiding document that will articulate threats to that species, propose methods to stabilize population declines, and ultimately increase their abundance. We have the ability to collect good data and make smart decisions for both wildlife and people. Nothing less will be required to ensure essential habitat in Idaho and other remaining wolverine strongholds continues to be hospitable for these rugged, iconic creatures. At the same time, ICL is redoubling our efforts to reverse human-caused climate change, the primary threat to wolverine. A comprehensive approach to make Idaho carbon neutral will not just benefit wolverines and other wildlife—but ourselves. As supporters of Idaho’s magnificent wildlife, we’ll also be asking for your involvement as this process begins to take shape. A handy Q & A page set up by USFWS can be found here.This landmark decision was not only science-driven, but it was the only logical conclusion we, as a country could make, if we hope to provide vital refuge for the last 300 wolverines in the lower 48 states and protect their future for generations to come.

ICL is troubled that the current listing proposal includes an exemption, allowing for the lawful “take” of a wolverine if it is incidentally injured or killed by traps intended to target other species. Since 1995, 11 wolverines have been accidentally captured in traps in Idaho, resulting in three mortalities. We also know that many of these events go unreported. We’ll be encouraging the USFWS to consider these issues and others as they draft a North American Wolverine Recovery Plan—the guiding document that will articulate threats to that species, propose methods to stabilize population declines, and ultimately increase their abundance. We have the ability to collect good data and make smart decisions for both wildlife and people. Nothing less will be required to ensure essential habitat in Idaho and other remaining wolverine strongholds continues to be hospitable for these rugged, iconic creatures. At the same time, ICL is redoubling our efforts to reverse human-caused climate change, the primary threat to wolverine. A comprehensive approach to make Idaho carbon neutral will not just benefit wolverines and other wildlife—but ourselves. As supporters of Idaho’s magnificent wildlife, we’ll also be asking for your involvement as this process begins to take shape. A handy Q & A page set up by USFWS can be found here.This landmark decision was not only science-driven, but it was the only logical conclusion we, as a country could make, if we hope to provide vital refuge for the last 300 wolverines in the lower 48 states and protect their future for generations to come.

Stay updated on news impacting Idaho wildlife by signing up for ICL Wildlife Campaign email udpates.