Kane Lake through watercolors: Re-creating adventure in the Salmon-Challis National Forest

The Salmon-Challis National Forest expands over 4.2 million acres of Idaho backcountry. The wildlands of the Salmon-Challis National Forest are largely roadless; they contain essential habitats for plant and wildlife species as well as crucial waterways for ecosystems and water use across central Idaho. To celebrate the importance of the Salmon-Challis National Forest, ICL will be publishing a blog series celebrating this vital land and the opportunities provided within.

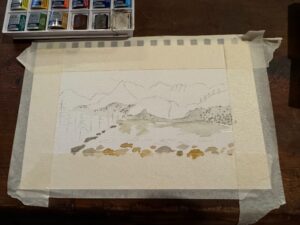

As an artist—even an amateur one—one of the great joys of creating a piece of art is revisiting its inspiration. As I’ve taken up watercolor painting, I find the act of translating a scene onto paper its own way of traveling back to the memory of that place, recalling it in greater detail, re-immersing into the subtleties of a moment. The first thing I do when sitting down to paint a scene is pull up a reference photo. From there, I place painter’s tape down on the edges of my paper for a clean, crisp line at the edge of the painting. I’ll take a mechanical pencil and sketch the bones of what I want to capture. And, of course, I’ll think back on my memory of the place. At ten years old, I went on my first backpacking trip. I was bound for a destination not too far from home, only an hour or so drive, but I felt that I might as well have been headed for the moon. I’d be traveling with some teachers and other children, aged ten to eighteen. I had no idea what to expect, other than some vague fears of the arduousness of hiking with a pack; my father had tried to take me on a few trudges around the neighborhood foothills to break the gear in, but he had a limited threshold for my complaining and general dislike of exercise. So off I went on my first trip, apprehensive and naive, mostly terrified and a tiny bit excited, with probably less than an hour’s experience wearing a backpack. After sketching a very approximate outline, I go in with my lightest colors. Since you cannot paint a light color over a dark color with watercolors, as is possible with oil or acrylic, it’s important to visualize what areas of the image will need to retain lighter shades. That becomes your first layer. For the lightest hues, I leave areas white—like the sky, for instance—knowing that the tiniest amount of pigment will go a long way.

At ten years old, I went on my first backpacking trip. I was bound for a destination not too far from home, only an hour or so drive, but I felt that I might as well have been headed for the moon. I’d be traveling with some teachers and other children, aged ten to eighteen. I had no idea what to expect, other than some vague fears of the arduousness of hiking with a pack; my father had tried to take me on a few trudges around the neighborhood foothills to break the gear in, but he had a limited threshold for my complaining and general dislike of exercise. So off I went on my first trip, apprehensive and naive, mostly terrified and a tiny bit excited, with probably less than an hour’s experience wearing a backpack. After sketching a very approximate outline, I go in with my lightest colors. Since you cannot paint a light color over a dark color with watercolors, as is possible with oil or acrylic, it’s important to visualize what areas of the image will need to retain lighter shades. That becomes your first layer. For the lightest hues, I leave areas white—like the sky, for instance—knowing that the tiniest amount of pigment will go a long way. After I’m satisfied with my lighter colors, I’ll go in with darker shades. I pay attention to my photo reference, looking closely at features in the rock or the color of the trees. I try my best to approximate shadows, thinking about where the light was at that moment.When we took off from the trailhead, we began weaving through lodgepole pines at a pace that felt just short of a jog for my sixth-grader legs. We stopped for our first snack, and I remember thinking, “Oh good, we must be about halfway.” We’d probably only traveled a mile. On we marched. While dismayed, tired, and feeling my legs begin to burn, something spectacular happened as we gained elevation and dropped from the trees: enormous, menacing mountain peaks began to frame the horizon, the likes of which I’d never seen so close. A mountain stream ran alongside the trail, every now and then revealing a white, multi-tiered waterfall, or a glassy green pool. Eventually, we found ourselves in a tremendous boulder field filled with the chirps of pikas, and I thought most certainly my legs would give out at any time now, but I was high above the valley we’d driven through that morning and amazed at the distance we’d covered.

After I’m satisfied with my lighter colors, I’ll go in with darker shades. I pay attention to my photo reference, looking closely at features in the rock or the color of the trees. I try my best to approximate shadows, thinking about where the light was at that moment.When we took off from the trailhead, we began weaving through lodgepole pines at a pace that felt just short of a jog for my sixth-grader legs. We stopped for our first snack, and I remember thinking, “Oh good, we must be about halfway.” We’d probably only traveled a mile. On we marched. While dismayed, tired, and feeling my legs begin to burn, something spectacular happened as we gained elevation and dropped from the trees: enormous, menacing mountain peaks began to frame the horizon, the likes of which I’d never seen so close. A mountain stream ran alongside the trail, every now and then revealing a white, multi-tiered waterfall, or a glassy green pool. Eventually, we found ourselves in a tremendous boulder field filled with the chirps of pikas, and I thought most certainly my legs would give out at any time now, but I was high above the valley we’d driven through that morning and amazed at the distance we’d covered. To fill negative spaces, water is your friend! I smudge droplets of water between pine trees, remembering less is more; the water’s natural fan across the paper will spread the pigment and add sublet texture, implying the shadows and bushes between the trees without having to illustrate them. For the sky, I fill the space in with only water; I then come back in with tiny drops of blue and grey, dabbing the brush gently to the still-wet paper. The pigment diffuses across the water, creating the feathery effect of clouds.Not long after reaching the boulder field, the oldest kids came trotting down the trail with the smug announcement that they’d already been up to the lake and picked the best campsites; they’d been up there so long and were so bored they decided to come back down the trail. The teachers smiled and made them take the packs of us sore, dragging youngsters. Soon the trail began to move a great deal faster. We crested into a meadow with scattered trees and car-sized boulders. A little further on, at last, we arrived at the lake. I thought I’d never, ever seen a place so beautiful, so wild.

To fill negative spaces, water is your friend! I smudge droplets of water between pine trees, remembering less is more; the water’s natural fan across the paper will spread the pigment and add sublet texture, implying the shadows and bushes between the trees without having to illustrate them. For the sky, I fill the space in with only water; I then come back in with tiny drops of blue and grey, dabbing the brush gently to the still-wet paper. The pigment diffuses across the water, creating the feathery effect of clouds.Not long after reaching the boulder field, the oldest kids came trotting down the trail with the smug announcement that they’d already been up to the lake and picked the best campsites; they’d been up there so long and were so bored they decided to come back down the trail. The teachers smiled and made them take the packs of us sore, dragging youngsters. Soon the trail began to move a great deal faster. We crested into a meadow with scattered trees and car-sized boulders. A little further on, at last, we arrived at the lake. I thought I’d never, ever seen a place so beautiful, so wild. For final touches, I use a fine, felt-tip black pen to outline smaller details. I add in snow on the peaks with light strokes of a white acrylic paint pen, which I also use to bring out some reflection of light on the water. I pull off the painter’s tape. And I catch myself smiling about my first-ever trip to a beautiful, treasured place in the Salmon-Challis National Forest: Kane Lake.I’ve gone many, many times again since I was ten; it’s the first hike I bring visitors—from boarding school friends to college friends, to my future husband—to demonstrate the hidden splendor just around the corner from where I grew up. Secluded and rugged, Kane Lake is a spectacular place for adventure, surrounded by staggering cliffs and hundred-foot waterfalls, framed by a grassy green meadow with purple heathers and yellow, red, and white wildflowers. It’s exactly the kind of place, as an amateur watercolor painter, that I like to adventure back to through my art.If you haven’t been to Kane Lake, let this inspire your own adventure — and if you’re brave, I encourage you to spend some time recreating it in the medium of your choice once you’re home. It could be a poem or an essay, a sketch or needlepoint, but experiment for yourself the magic of revisiting an adventure through art.

For final touches, I use a fine, felt-tip black pen to outline smaller details. I add in snow on the peaks with light strokes of a white acrylic paint pen, which I also use to bring out some reflection of light on the water. I pull off the painter’s tape. And I catch myself smiling about my first-ever trip to a beautiful, treasured place in the Salmon-Challis National Forest: Kane Lake.I’ve gone many, many times again since I was ten; it’s the first hike I bring visitors—from boarding school friends to college friends, to my future husband—to demonstrate the hidden splendor just around the corner from where I grew up. Secluded and rugged, Kane Lake is a spectacular place for adventure, surrounded by staggering cliffs and hundred-foot waterfalls, framed by a grassy green meadow with purple heathers and yellow, red, and white wildflowers. It’s exactly the kind of place, as an amateur watercolor painter, that I like to adventure back to through my art.If you haven’t been to Kane Lake, let this inspire your own adventure — and if you’re brave, I encourage you to spend some time recreating it in the medium of your choice once you’re home. It could be a poem or an essay, a sketch or needlepoint, but experiment for yourself the magic of revisiting an adventure through art.