In Her Death, 399 is a Champion for Wildlife-Friendly Highways

Vexing, yet sometimes complex conservation issues like wildlife connectivity and landscape fragmentation almost never come into stark relief for the general public. However, the news jolt of the unceremonious death of Grizzly 399 cascaded through media outlets not just across the country, but across the world. In her final act, the “Queen of the Tetons” immediately crystalised the need to make perilous travel corridors safer for animals.The matriarch of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem had likely been traversing the Snake River Canyon seeking high-calorie food sources in one final push to get herself and her yearling cub fattened up before denning season—an annual lifecycle phase known as hyperphagia. The unmatched embodiment of the wild, rugged west, her vulnerability was a shock to our systems. However, her elemental pursuit of food to make it through another winter tracks with the plight of dozens of other species. The ability for these animals to move safely between habitat types is critical to their survival. With each day, science continues to show us the importance of wildlife movement corridors. Finding ways to re-integrate disconnected habitats to allow wild creatures to be more resilient to new threats, individually and as a population, is one of the biggest conservation challenges of our time.Public lands management, industrial and residential development, and climate change all play a role in contributing to habitat fragmentation. However, highway infrastructure and the physical barriers presented by America’s four million miles of roadways are the primary factors in preventing natural movement of animals across a landscape. Many western states are making incremental progress to understand the seasonal needs of native wildlife and minimize impacts to wildlife from highway systems—but it can’t seem to happen fast enough. In fact, 399 was hit and killed only miles from a site that the Teton County Wildlife Crossing Master Plan previously identified as an important wildlife movement corridor and the potential location of a highway infrastructure project.Strategically located structures near heavily used wildlife crossing areas have been shown to reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions by 80 percent or more. As our state continues to see record growth and visitation, threats to wildlife from motor vehicles are only going to increase. Infrastructure projects take years, sometimes decades, to design and build. But, Idaho has no such highway crossings “master plan” that accounts for wildlife. With almost 90% of Idahoans supporting efforts to build migration route crossings, those popular sentiments still haven’t translated to widespread action in our state. Unfortunately, even compelling projects like a proposal at Targhee Pass—where iconic animals from Yellowstone seek routes to milder winter ranges—have been derailed by blustery voices with outsized self-interests. Even with an abundance of new federal funding available to transportation departments all across the country, Idaho lags behind almost all western states in prioritizing and long-term planning for wildlife-friendly infrastructure. There are tiny glimmers of hope, however. My recent tour of the new, award-winning Cervidae Peak wildlife overpass does show that public support can lead to collaboration between Idaho Department of Fish and Game (IDFG) biologists and Idaho Transportation Department (ITD), helping to make at least a small part of our state safer for native wildlife like deer and elk. As a “first of its kind” effort in Idaho, the Cervidae Peak Overpass is an important pilot project. The Boise River Wildlife Management Area (BRWMA), just north of Lucky Peak Reservoir, hosts many of the animals that now benefit from the new crossing structure. Some 8,000-10,000 mule deer and elk use the “Mores Creek Arm” of the reservoir to travel up Deer Creek and into BRWMA winter range. Tracking evidence has shown that GPS-collared deer have traveled over 40 miles to access that habitat, which burned extensively in last month’s Valley Fire. Fire events that impact large tracts of historic winter range further fragment the landscape and make access to remaining essential healthy habitat even more important. Crossing structures like Cervidae Peak can help accomplish this.

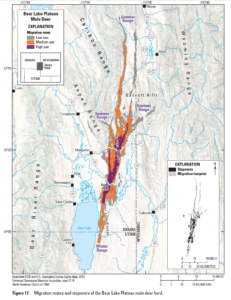

My recent tour of the new, award-winning Cervidae Peak wildlife overpass does show that public support can lead to collaboration between Idaho Department of Fish and Game (IDFG) biologists and Idaho Transportation Department (ITD), helping to make at least a small part of our state safer for native wildlife like deer and elk. As a “first of its kind” effort in Idaho, the Cervidae Peak Overpass is an important pilot project. The Boise River Wildlife Management Area (BRWMA), just north of Lucky Peak Reservoir, hosts many of the animals that now benefit from the new crossing structure. Some 8,000-10,000 mule deer and elk use the “Mores Creek Arm” of the reservoir to travel up Deer Creek and into BRWMA winter range. Tracking evidence has shown that GPS-collared deer have traveled over 40 miles to access that habitat, which burned extensively in last month’s Valley Fire. Fire events that impact large tracts of historic winter range further fragment the landscape and make access to remaining essential healthy habitat even more important. Crossing structures like Cervidae Peak can help accomplish this.  In another part of the state, wildlife movement data compiled by IDFG and United States Geological Survey researchers has shown mule deer making seasonal use of hundreds of miles of habitat near Montpelier, while ranging as far as Wyoming and Utah. The migration bottleneck, known as Rocky Point, has been identified as providing critical access to winter range for the Bear Lake Plateau Mule Deer herd and will be the site of Idaho’s second major infrastructure project. The herd is a case study in the migration gauntlets that distinct groups of animals encounter as they move between seasonal ranges. Here, animals moving out of the Aspen and Caribou Ranges in Idaho and the Gannett Hills in Wyoming are funneled into an area restricted by the Bear River, US Highway 30, and Union Pacific’s Oregon Short Line Railway. The herd must also navigate miles of unfriendly fencing and mining developments in their summer range.Earlier this year, ICL highlighted how interstate freeways, like I-90 in North Idaho, prevent grizzly bears from moving between recovery zones for the ESA-listed species. The Bitterroot area, a chunk of nearly 6,000 square miles of central Idaho’s wildlands, is the last remaining expanse of unoccupied habitat identified in the 1993 federal recovery plan for grizzly bears. ICL would prefer to see bears move into this area on their own, without human intervention. The first animals seeking to pioneer into this country would likely come from the north, originating from source grizzly populations in the Selkirk/Cabinet-Yaak or North Continental Divide ecosystems. Wildlife crossings, even modest highway underpasses, could help facilitate these movements, and minimize the potential for horrible outcomes like we just witnessed in Teton County. Infrastructure modifications are likely the only way grizzlies from the north will be able to anchor a new population in Bitterroot country.Not too far east, on the Flathead Indian Reservation in west-central Montana, the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes (CSKT) led successful efforts to build an overpass on US Highway 93 in 2009. The “Animal’s Bridge,” now a part of the landscape on the way to the CSKT Bison Range, was constructed with a design ethic of “protecting cultural, aesthetic, recreational, and natural resources located along the highway corridor and communicating the respect and value commonly held for these resources pursuant to traditional ways of the Tribes.” The span is now part of a 60-mile stretch of interstate that boasts the highest density of highway crossing features in the country. Next year, with the help from the Federal Highway Administration’s Wildlife Crossings Pilot Program, another overpass will be built 30 miles to the north, near the Ninepipe National Wildlife Management Area. Camera traps nearby have recorded grizzlies using underpasses on almost two-dozen occasions.

In another part of the state, wildlife movement data compiled by IDFG and United States Geological Survey researchers has shown mule deer making seasonal use of hundreds of miles of habitat near Montpelier, while ranging as far as Wyoming and Utah. The migration bottleneck, known as Rocky Point, has been identified as providing critical access to winter range for the Bear Lake Plateau Mule Deer herd and will be the site of Idaho’s second major infrastructure project. The herd is a case study in the migration gauntlets that distinct groups of animals encounter as they move between seasonal ranges. Here, animals moving out of the Aspen and Caribou Ranges in Idaho and the Gannett Hills in Wyoming are funneled into an area restricted by the Bear River, US Highway 30, and Union Pacific’s Oregon Short Line Railway. The herd must also navigate miles of unfriendly fencing and mining developments in their summer range.Earlier this year, ICL highlighted how interstate freeways, like I-90 in North Idaho, prevent grizzly bears from moving between recovery zones for the ESA-listed species. The Bitterroot area, a chunk of nearly 6,000 square miles of central Idaho’s wildlands, is the last remaining expanse of unoccupied habitat identified in the 1993 federal recovery plan for grizzly bears. ICL would prefer to see bears move into this area on their own, without human intervention. The first animals seeking to pioneer into this country would likely come from the north, originating from source grizzly populations in the Selkirk/Cabinet-Yaak or North Continental Divide ecosystems. Wildlife crossings, even modest highway underpasses, could help facilitate these movements, and minimize the potential for horrible outcomes like we just witnessed in Teton County. Infrastructure modifications are likely the only way grizzlies from the north will be able to anchor a new population in Bitterroot country.Not too far east, on the Flathead Indian Reservation in west-central Montana, the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes (CSKT) led successful efforts to build an overpass on US Highway 93 in 2009. The “Animal’s Bridge,” now a part of the landscape on the way to the CSKT Bison Range, was constructed with a design ethic of “protecting cultural, aesthetic, recreational, and natural resources located along the highway corridor and communicating the respect and value commonly held for these resources pursuant to traditional ways of the Tribes.” The span is now part of a 60-mile stretch of interstate that boasts the highest density of highway crossing features in the country. Next year, with the help from the Federal Highway Administration’s Wildlife Crossings Pilot Program, another overpass will be built 30 miles to the north, near the Ninepipe National Wildlife Management Area. Camera traps nearby have recorded grizzlies using underpasses on almost two-dozen occasions. Local communities can be effective messengers working on behalf of safe passageways for wildlife. Back here in Idaho, staff at IDFG, ITD, Governor Little’s office, and our elected federal delegation deserve to hear from advocates about the importance of bringing more of these projects to wildlife-vehicle collision hotspots in our state.According to estimates from the Wildlands Network, over three-quarters of all habitat connectivity legislation has been passed in just the last five years. Recently introduced proposals like the Wildlife Movement Through Partnerships Act and the Wildlife Corridors and Habitat Connectivity Conservation Act that address habitat fragmentation and connectivity deserve the support of wildlife advocates. The initiatives could build on Bipartisan Infrastructure Law funding to conserve habitat quality in movement areas, modify fencing to make it more wildlife-friendly, enhance research and mapping efforts, incentivize private landowners for wildlife accommodations, and build more crossing structures.Wildlife crossings and highway infrastructure are by no means the only issue in the wildlife-human domain of conflicts. ICL has continued to raise concerns about the need for reasonable, proactive food storage rules on public lands and the wider use of nonlethal methods to address presence of large carnivores near livestock. However, we also strongly believe it’s time for Idaho to join efforts of neighboring states to recognize and address the challenges presented to migratory wildlife by highway infrastructure.

Local communities can be effective messengers working on behalf of safe passageways for wildlife. Back here in Idaho, staff at IDFG, ITD, Governor Little’s office, and our elected federal delegation deserve to hear from advocates about the importance of bringing more of these projects to wildlife-vehicle collision hotspots in our state.According to estimates from the Wildlands Network, over three-quarters of all habitat connectivity legislation has been passed in just the last five years. Recently introduced proposals like the Wildlife Movement Through Partnerships Act and the Wildlife Corridors and Habitat Connectivity Conservation Act that address habitat fragmentation and connectivity deserve the support of wildlife advocates. The initiatives could build on Bipartisan Infrastructure Law funding to conserve habitat quality in movement areas, modify fencing to make it more wildlife-friendly, enhance research and mapping efforts, incentivize private landowners for wildlife accommodations, and build more crossing structures.Wildlife crossings and highway infrastructure are by no means the only issue in the wildlife-human domain of conflicts. ICL has continued to raise concerns about the need for reasonable, proactive food storage rules on public lands and the wider use of nonlethal methods to address presence of large carnivores near livestock. However, we also strongly believe it’s time for Idaho to join efforts of neighboring states to recognize and address the challenges presented to migratory wildlife by highway infrastructure.  The nation’s gaze has turned toward the literal intersection of human-wildlife conflicts. New research is systematically mapping animal movements that have been common knowledge of locals for generations. Infrastructure projects offering permeability for wildlife also make roads safer for humans and pay for themselves over time. National spending priorities have given us an opportunity to tap into huge new pools of funding for crossing projects in priority areas all across Idaho. Let’s leverage overwhelming public support for effective crossing structures to benefit our state’s wildlife and our economy. Tragic incidents involving charismatic wildlife like Grizzly 399 give us all a growing sense that we must do more to make sure both humans and wildlife can get to places they need to go. We know how to make travel less dangerous for Idahoans and the animals all of us love. Let’s tell Idaho’s leaders that urgency is needed to seize this once-in-a-generation opportunity to make roadways work for people and the animals we all love. Please join ICL in asking state leaders and our congressional delegation to seek funding opportunities to build crossing structures in known wildlife-vehicle collision priority areas and to support the Wildlife Movement Through Partnerships and Wildlife Corridors and Habitat Connectivity Conservation Acts. You can do so by taking action at the link below!

The nation’s gaze has turned toward the literal intersection of human-wildlife conflicts. New research is systematically mapping animal movements that have been common knowledge of locals for generations. Infrastructure projects offering permeability for wildlife also make roads safer for humans and pay for themselves over time. National spending priorities have given us an opportunity to tap into huge new pools of funding for crossing projects in priority areas all across Idaho. Let’s leverage overwhelming public support for effective crossing structures to benefit our state’s wildlife and our economy. Tragic incidents involving charismatic wildlife like Grizzly 399 give us all a growing sense that we must do more to make sure both humans and wildlife can get to places they need to go. We know how to make travel less dangerous for Idahoans and the animals all of us love. Let’s tell Idaho’s leaders that urgency is needed to seize this once-in-a-generation opportunity to make roadways work for people and the animals we all love. Please join ICL in asking state leaders and our congressional delegation to seek funding opportunities to build crossing structures in known wildlife-vehicle collision priority areas and to support the Wildlife Movement Through Partnerships and Wildlife Corridors and Habitat Connectivity Conservation Acts. You can do so by taking action at the link below!

TAKE ACTION

To volunteer with IDFG for Valley and Paddock Fire restoration activities, click HERE!